Developer Guide

This guide is intended for people who want to work on Spack itself. If you just want to develop packages, see the Packaging Guide.

It is assumed that you’ve read the Basic Usage and Packaging Guide sections, and that you’re familiar with the concepts discussed there. If you’re not, we recommend reading those first.

Overview

Spack is designed with three separate roles in mind:

Users, who need to install software without knowing all the details about how it is built.

Packagers who know how a particular software package is built and encode this information in package files.

Developers who work on Spack, add new features, and try to make the jobs of packagers and users easier.

Users could be end users installing software in their home directory, or administrators installing software to a shared directory on a shared machine. Packagers could be administrators who want to automate software builds, or application developers who want to make their software more accessible to users.

As you might expect, there are many types of users with different

levels of sophistication, and Spack is designed to accommodate both

simple and complex use cases for packages. A user who only knows that

he needs a certain package should be able to type something simple,

like spack install <package name>, and get the package that he

wants. If a user wants to ask for a specific version, use particular

compilers, or build several versions with different configurations,

then that should be possible with a minimal amount of additional

specification.

This gets us to the two key concepts in Spack’s software design:

Specs: expressions for describing builds of software, and

Packages: Python modules that build software according to a spec.

A package is a template for building particular software, and a spec as a descriptor for one or more instances of that template. Users express the configuration they want using a spec, and a package turns the spec into a complete build.

The obvious difficulty with this design is that users under-specify what they want. To build a software package, the package object needs a complete specification. In Spack, if a spec describes only one instance of a package, then we say it is concrete. If a spec could describes many instances, (i.e. it is under-specified in one way or another), then we say it is abstract.

Spack’s job is to take an abstract spec from the user, find a concrete spec that satisfies the constraints, and hand the task of building the software off to the package object. The rest of this document describes all the pieces that come together to make that happen.

Directory Structure

So that you can familiarize yourself with the project, we’ll start with a high level view of Spack’s directory structure:

spack/ <- installation root

bin/

spack <- main spack executable

etc/

spack/ <- Spack config files.

Can be overridden by files in ~/.spack.

var/

spack/ <- build & stage directories

repos/ <- contains package repositories

builtin/ <- pkg repository that comes with Spack

repo.yaml <- descriptor for the builtin repository

packages/ <- directories under here contain packages

cache/ <- saves resources downloaded during installs

opt/

spack/ <- packages are installed here

lib/

spack/

docs/ <- source for this documentation

env/ <- compiler wrappers for build environment

external/ <- external libs included in Spack distro

llnl/ <- some general-use libraries

spack/ <- spack module; contains Python code

build_systems/ <- modules for different build systems

cmd/ <- each file in here is a spack subcommand

compilers/ <- compiler description files

container/ <- module for spack containerize

hooks/ <- hook modules to run at different points

modules/ <- modules for lmod, tcl, etc.

operating_systems/ <- operating system modules

platforms/ <- different spack platforms

reporters/ <- reporters like cdash, junit

schema/ <- schemas to validate data structures

solver/ <- the spack solver

test/ <- unit test modules

util/ <- common code

Spack is designed so that it could live within a standard UNIX

directory hierarchy, so lib,

var, and opt all contain a spack subdirectory in case

Spack is installed alongside other software. Most of the interesting

parts of Spack live in lib/spack.

Spack has one directory layout and there is no install process.

Most Python programs don’t look like this (they use distutils, setup.py,

etc.) but we wanted to make Spack very easy to use. The simple layout

spares users from the need to install Spack into a Python environment.

Many users don’t have write access to a Python installation, and installing

an entire new instance of Python to bootstrap Spack would be very complicated.

Users should not have to install a big, complicated package to

use the thing that’s supposed to spare them from the details of big,

complicated packages. The end result is that Spack works out of the

box: clone it and add bin to your PATH and you’re ready to go.

Code Structure

This section gives an overview of the various Python modules in Spack, grouped by functionality.

Build environment

spack.stageHandles creating temporary directories for builds.

spack.build_environmentThis contains utility functions used by the compiler wrapper script,

cc.spack.directory_layoutClasses that control the way an installation directory is laid out. Create more implementations of this to change the hierarchy and naming scheme in

$spack_prefix/opt

Spack Subcommands

spack.cmdEach module in this package implements a Spack subcommand. See writing commands for details.

Unit tests

spack.testImplements Spack’s test suite. Add a module and put its name in the test suite in

__init__.pyto add more unit tests.

Other Modules

spack.urlURL parsing, for deducing names and versions of packages from tarball URLs.

spack.errorSpackError, the base class for Spack’s exception hierarchy.llnl.util.ttyBasic output functions for all of the messages Spack writes to the terminal.

llnl.util.tty.colorImplements a color formatting syntax used by

spack.tty.llnl.utilIn this package are a number of utility modules for the rest of Spack.

Spec objects

Package objects

Most spack commands look something like this:

Parse an abstract spec (or specs) from the command line,

Normalize the spec based on information in package files,

Concretize the spec according to some customizable policies,

Instantiate a package based on the spec, and

Call methods (e.g.,

install()) on the package object.

The information in Package files is used at all stages in this process.

Writing commands

Adding a new command to Spack is easy. Simply add a <name>.py file to

lib/spack/spack/cmd/, where <name> is the name of the subcommand.

At the bare minimum, two functions are required in this file:

setup_parser()

Unless your command doesn’t accept any arguments, a setup_parser()

function is required to define what arguments and flags your command takes.

See the Argparse documentation

for more details on how to add arguments.

Some commands have a set of subcommands, like spack compiler find or

spack module lmod refresh. You can add subparsers to your parser to handle

this. Check out spack edit --command compiler for an example of this.

A lot of commands take the same arguments and flags. These arguments should

be defined in lib/spack/spack/cmd/common/arguments.py so that they don’t

need to be redefined in multiple commands.

<name>()

In order to run your command, Spack searches for a function with the same

name as your command in <name>.py. This is the main method for your

command, and can call other helper methods to handle common tasks.

Remember, before adding a new command, think to yourself whether or not this new command is actually necessary. Sometimes, the functionality you desire can be added to an existing command. Also remember to add unit tests for your command. If it isn’t used very frequently, changes to the rest of Spack can cause your command to break without sufficient unit tests to prevent this from happening.

Whenever you add/remove/rename a command or flags for an existing command, make sure to update Spack’s Bash tab completion script.

Writing Hooks

A hook is a callback that makes it easy to design functions that run for different events. We do this by way of defining hook types, and then inserting them at different places in the spack code base. Whenever a hook type triggers by way of a function call, we find all the hooks of that type, and run them.

Spack defines hooks by way of a module at lib/spack/spack/hooks where we can define

types of hooks in the __init__.py, and then python files in that folder

can use hook functions. The files are automatically parsed, so if you write

a new file for some integration (e.g., lib/spack/spack/hooks/myintegration.py

you can then write hook functions in that file that will be automatically detected,

and run whenever your hook is called. This section will cover the basic kind

of hooks, and how to write them.

Types of Hooks

The following hooks are currently implemented to make it easy for you, the developer, to add hooks at different stages of a spack install or similar. If there is a hook that you would like and is missing, you can propose to add a new one.

pre_install(spec)

A pre_install hook is run within the install subprocess, directly before the install starts.

It expects a single argument of a spec.

post_install(spec, explicit=None)

A post_install hook is run within the install subprocess, directly after the install finishes,

but before the build stage is removed and the spec is registered in the database. It expects two

arguments: spec and an optional boolean indicating whether this spec is being installed explicitly.

pre_uninstall(spec) and post_uninstall(spec)

These hooks are currently used for cleaning up module files after uninstall.

Adding a New Hook Type

Adding a new hook type is very simple! In lib/spack/spack/hooks/__init__.py

you can simply create a new HookRunner that is named to match your new hook.

For example, let’s say you want to add a new hook called post_log_write

to trigger after anything is written to a logger. You would add it as follows:

# pre/post install and run by the install subprocess

pre_install = HookRunner('pre_install')

post_install = HookRunner('post_install')

# hooks related to logging

post_log_write = HookRunner('post_log_write') # <- here is my new hook!

You then need to decide what arguments my hook would expect. Since this is

related to logging, let’s say that you want a message and level. That means

that when you add a python file to the lib/spack/spack/hooks

folder with one or more callbacks intended to be triggered by this hook. You might

use my new hook as follows:

def post_log_write(message, level):

"""Do something custom with the message and level every time we write

to the log

"""

print('running post_log_write!')

To use the hook, we would call it as follows somewhere in the logic to do logging. In this example, we use it outside of a logger that is already defined:

import spack.hooks

# We do something here to generate a logger and message

spack.hooks.post_log_write(message, logger.level)

This is not to say that this would be the best way to implement an integration with the logger (you’d probably want to write a custom logger, or you could have the hook defined within the logger) but serves as an example of writing a hook.

Unit tests

Unit testing

Developer environment

Warning

This is an experimental feature. It is expected to change and you should not use it in a production environment.

When installing a package, we currently have support to export environment variables to specify adding debug flags to the build. By default, a package install will build without any debug flag. However, if you want to add them, you can export:

export SPACK_ADD_DEBUG_FLAGS=true

spack install zlib

If you want to add custom flags, you should export an additional variable:

export SPACK_ADD_DEBUG_FLAGS=true

export SPACK_DEBUG_FLAGS="-g"

spack install zlib

These environment variables will eventually be integrated into spack so they are set from the command line.

Developer commands

spack doc

spack style

spack style exists to help the developer user to check imports and style with mypy, flake8, isort, and (soon) black. To run all style checks, simply do:

$ spack style

To run automatic fixes for isort you can do:

$ spack style --fix

You do not need any of these Python packages installed on your system for the checks to work! Spack will bootstrap install them from packages for your use.

spack unit-test

See the contributor guide section on

spack unit-test.

spack python

spack python is a command that lets you import and debug things as if

you were in a Spack interactive shell. Without any arguments, it is similar

to a normal interactive Python shell, except you can import spack and any

other Spack modules:

$ spack python

Spack version 0.10.0

Python 2.7.13, Linux x86_64

>>> from spack.version import Version

>>> a = Version('1.2.3')

>>> b = Version('1_2_3')

>>> a == b

True

>>> c = Version('1.2.3b')

>>> c > a

True

>>>

If you prefer using an IPython interpreter, given that IPython is installed

you can specify the interpreter with -i:

$ spack python -i ipython

Python 3.8.3 (default, May 19 2020, 18:47:26)

Type 'copyright', 'credits' or 'license' for more information

IPython 7.17.0 -- An enhanced Interactive Python. Type '?' for help.

Spack version 0.16.0

Python 3.8.3, Linux x86_64

In [1]:

With either interpreter you can run a single command:

$ spack python -c 'from spack.spec import Spec; Spec("python").concretized()'

...

$ spack python -i ipython -c 'from spack.spec import Spec; Spec("python").concretized()'

Out[1]: ...

or a file:

$ spack python ~/test_fetching.py

$ spack python -i ipython ~/test_fetching.py

just like you would with the normal python command.

spack blame

Spack blame is a way to quickly see contributors to packages or files in the spack repository. You should provide a target package name or file name to the command. Here is an example asking to see contributions for the package “python”:

$ spack blame python

LAST_COMMIT LINES % AUTHOR EMAIL

2 weeks ago 3 0.3 Mickey Mouse <cheddar@gmouse.org>

a month ago 927 99.7 Minnie Mouse <swiss@mouse.org>

2 weeks ago 930 100.0

By default, you will get a table view (shown above) sorted by date of contribution,

with the most recent contribution at the top. If you want to sort instead

by percentage of code contribution, then add -p:

$ spack blame -p python

And to see the git blame view, add -g instead:

$ spack blame -g python

Finally, to get a json export of the data, add --json:

$ spack blame --json python

spack url

A package containing a single URL can be used to download several different

versions of the package. If you’ve ever wondered how this works, all of the

magic is in spack.url. This module contains methods for extracting

the name and version of a package from its URL. The name is used by

spack create to guess the name of the package. By determining the version

from the URL, Spack can replace it with other versions to determine where to

download them from.

The regular expressions in parse_name_offset and parse_version_offset

are used to extract the name and version, but they aren’t perfect. In order

to debug Spack’s URL parsing support, the spack url command can be used.

spack url parse

If you need to debug a single URL, you can use the following command:

$ spack url parse http://cache.ruby-lang.org/pub/ruby/2.2/ruby-2.2.0.tar.gz

==> Parsing URL: http://cache.ruby-lang.org/pub/ruby/2.2/ruby-2.2.0.tar.gz

==> Matched version regex 0: r'^[a-zA-Z+._-]+[._-]v?(\\d[\\d._-]*)$'

==> Matched name regex 10: r'^([A-Za-z\\d+\\._-]+)$'

==> Detected:

http://cache.ruby-lang.org/pub/ruby/2.2/ruby-2.2.0.tar.gz

---- ~~~~~

name: ruby

version: 2.2.0

==> Substituting version 9.9.9b:

http://cache.ruby-lang.org/pub/ruby/2.2/ruby-9.9.9b.tar.gz

---- ~~~~~~

You’ll notice that the name and version of this URL are correctly detected,

and you can even see which regular expressions it was matched to. However,

you’ll notice that when it substitutes the version number in, it doesn’t

replace the 2.2 with 9.9 where we would expect 9.9.9b to live.

This particular package may require a list_url or url_for_version

function.

This command also accepts a --spider flag. If provided, Spack searches

for other versions of the package and prints the matching URLs.

spack url list

This command lists every URL in every package in Spack. If given the

--color and --extrapolation flags, it also colors the part of

the string that it detected to be the name and version. The

--incorrect-name and --incorrect-version flags can be used to

print URLs that were not being parsed correctly.

spack url summary

This command attempts to parse every URL for every package in Spack and prints a summary of how many of them are being correctly parsed. It also prints a histogram showing which regular expressions are being matched and how frequently:

$ spack url summary

==> Generating a summary of URL parsing in Spack...

Total URLs found: 7881

Names correctly parsed: 6847/7881 (86.88%)

Versions correctly parsed: 6930/7881 (87.93%)

==> Statistics on name regular expressions:

Index Right Wrong Total Regular Expression

0 1837 367 2204 r'github\\.com/[^/]+/([^/]+)'

1 6 0 6 r'gitlab[^/]+/api/v4/projects/[^/]+%2F([^/]+)'

2 65 27 92 r'gitlab[^/]+/(?!api/v4/projects)[^/]+/([^/]+)'

3 16 6 22 r'bitbucket\\.org/[^/]+/([^/]+)'

4 4 0 4 r'pypi\\.(?:python\\.org|io)/packages/source/[A-Za-z\\d]/([^/]+)'

6 13 1 14 r'\\?f=([A-Za-z\\d+-]+)$'

7 21 0 21 r'\\?package=([A-Za-z\\d+-]+)'

9 2 1 3 r'([^/]+)/download.php$'

10 4883 602 5485 r'^([A-Za-z\\d+\\._-]+)$'

==> Statistics on version regular expressions:

Index Right Wrong Total Regular Expression

0 4939 197 5136 r'^[a-zA-Z+._-]+[._-]v?(\\d[\\d._-]*)$'

1 1425 67 1492 r'^v?(\\d[\\d._-]*)$'

2 14 38 52 r'^[a-zA-Z+]*(\\d[\\da-zA-Z]*)$'

3 10 17 27 r'^[a-zA-Z+-]*(\\d[\\da-zA-Z-]*)$'

4 7 128 135 r'^[a-zA-Z+_]*(\\d[\\da-zA-Z_]*)$'

5 61 28 89 r'^[a-zA-Z+.]*(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

6 277 10 287 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+-]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

7 1 0 1 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+-]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z_]*)$'

8 34 1 35 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+_]+_v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

9 0 2 2 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+_]+\\.v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

10 0 1 1 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+]+_r?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z-]*)$'

11 31 81 112 r'^(?:[a-zA-Z\\d+-]+-)?v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.-]*)$'

12 3 0 3 r'^[a-zA-Z+]+v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.-]*)$'

13 12 4 16 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+_]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

14 28 7 35 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+.]+_v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.-]*)$'

15 1 0 1 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+-]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._]*)$'

16 3 1 4 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+._]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

17 5 1 6 r'^[a-zA-Z+-]+(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._]*)$'

18 1 2 3 r'^[a-zA-Z\\d+_-]+-v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)$'

19 0 1 1 r'bzr(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._-]*)$'

20 10 0 10 r'[?&](?:sha|ref|version)=[a-zA-Z\\d+-]*[_-]?v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._-]*)$'

21 35 0 35 r'[?&](?:filename|f|get)=[a-zA-Z\\d+-]+[_-]v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z.]*)'

22 14 1 15 r'github\\.com/[^/]+/[^/]+/releases/download/[a-zA-Z+._-]*v?(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._-]*)/'

23 19 253 272 r'(\\d[\\da-zA-Z._-]*)/[^/]+$'

This command is essential for anyone adding or changing the regular expressions that parse names and versions. By running this command before and after the change, you can make sure that your regular expression fixes more packages than it breaks.

Profiling

Spack has some limited built-in support for profiling, and can report

statistics using standard Python timing tools. To use this feature,

supply --profile to Spack on the command line, before any subcommands.

spack --profile

spack --profile output looks like this:

$ spack --profile graph hdf5

o hdf5@1.14.3/txo3zeu

|\

| |\

| | |\

| | | |\

| | | | |\

| | | | | |\

| | o | | | | openmpi@5.0.3/ienqgou

| |/| | | | |

|/|/| | | | |

| | |\| | | |

| | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | | | | | |\ \ \ \ \

| | | | | | | | | | |_|/ / /

| | | | | | | | | |/| | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |\ \ \ \

| | | | | | | | | | | |_|/ /

| | | | | | | | | | |/| | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |\ \ \

...

The bottom of the output shows the top most time consuming functions, slowest on top. The profiling support is from Python’s built-in tool, cProfile.

Releases

This section documents Spack’s release process. It is intended for project maintainers, as the tasks described here require maintainer privileges on the Spack repository. For others, we hope this section at least provides some insight into how the Spack project works.

Release branches

There are currently two types of Spack releases: major releases (0.17.0, 0.18.0, etc.) and point releases (0.17.1, 0.17.2, 0.17.3, etc.). Here is a

diagram of how Spack release branches work:

o branch: develop (latest version, v0.19.0.dev0)

|

o

| o branch: releases/v0.18, tag: v0.18.1

o |

| o tag: v0.18.0

o |

| o

|/

o

|

o

| o branch: releases/v0.17, tag: v0.17.2

o |

| o tag: v0.17.1

o |

| o tag: v0.17.0

o |

| o

|/

o

The develop branch has the latest contributions, and nearly all pull

requests target develop. The develop branch will report that its

version is that of the next major release with a .dev0 suffix.

Each Spack release series also has a corresponding branch, e.g.

releases/v0.18 has 0.18.x versions of Spack, and

releases/v0.17 has 0.17.x versions. A major release is the first

tagged version on a release branch. Minor releases are back-ported from

develop onto release branches. This is typically done by cherry-picking

bugfix commits off of develop.

To avoid version churn for users of a release series, minor releases should not make changes that would change the concretization of packages. They should generally only contain fixes to the Spack core. However, sometimes priorities are such that new functionality needs to be added to a minor release.

Both major and minor releases are tagged. As a convenience, we also tag

the latest release as releases/latest, so that users can easily check

it out to get the latest stable version. See Updating releases/latest

for more details.

Scheduling work for releases

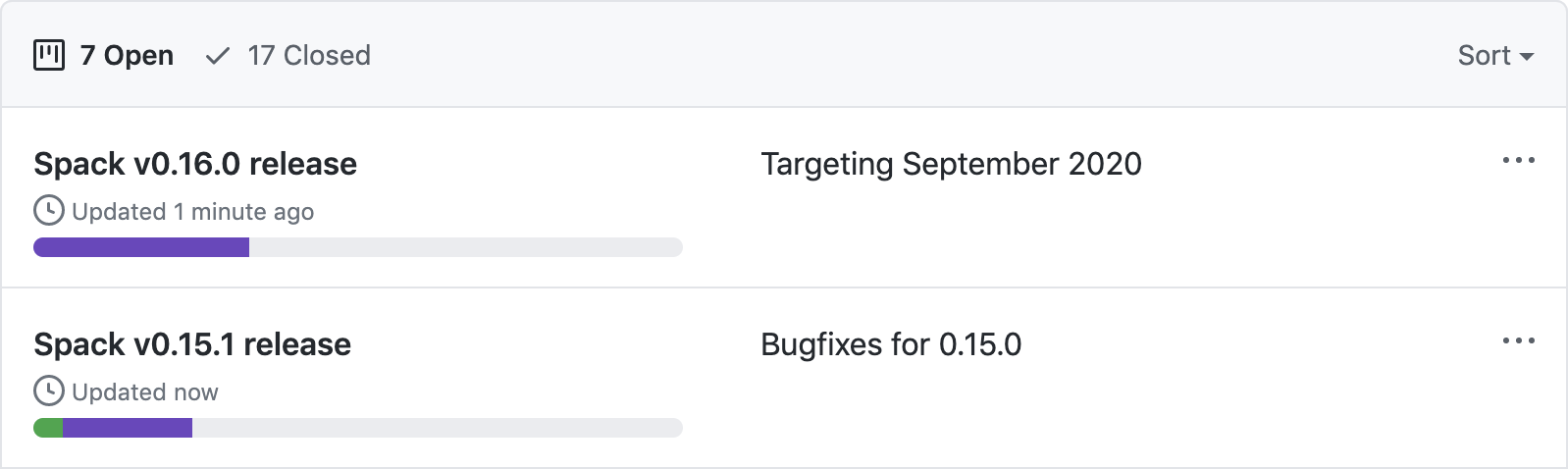

We schedule work for releases by creating GitHub projects. At any time, there may be several open release projects. For example, below are two releases (from some past version of the page linked above):

This image shows one release in progress for 0.15.1 and another for

0.16.0. Each of these releases has a project board containing issues

and pull requests. GitHub shows a status bar with completed work in

green, work in progress in purple, and work not started yet in gray, so

it’s fairly easy to see progress.

Spack’s project boards are not firm commitments so we move work between releases frequently. If we need to make a release and some tasks are not yet done, we will simply move them to the next minor or major release, rather than delaying the release to complete them.

For more on using GitHub project boards, see GitHub’s documentation.

Making major releases

Assuming a project board has already been created and all required work completed, the steps to make the major release are:

Create two new project boards:

One for the next major release

One for the next point release

Move any optional tasks that are not done to one of the new project boards.

In general, small bugfixes should go to the next point release. Major features, refactors, and changes that could affect concretization should go in the next major release.

Create a branch for the release, based on

develop:$ git checkout -b releases/v0.15 develop

For a version

vX.Y.Z, the branch’s name should bereleases/vX.Y. That is, you should create areleases/vX.Ybranch if you are preparing theX.Y.0release.Remove the

dev0development release segment from the version tuple inlib/spack/spack/__init__.py.The version number itself should already be correct and should not be modified.

Update

CHANGELOG.mdwith major highlights in bullet form.Use proper markdown formatting, like this example from 0.15.0.

Push the release branch to GitHub.

Make sure CI passes on the release branch, including:

Regular unit tests

Build tests

The E4S pipeline at gitlab.spack.io

If CI is not passing, submit pull requests to

developas normal and keep rebasing the release branch ondevelopuntil CI passes.Make sure the entire documentation is up to date. If documentation is outdated submit pull requests to

developas normal and keep rebasing the release branch ondevelop.Bump the major version in the

developbranch.Create a pull request targeting the

developbranch, bumping the major version inlib/spack/spack/__init__.pywith adev0release segment. For instance when you have just releasedv0.15.0, set the version to(0, 16, 0, 'dev0')ondevelop.Follow the steps in Publishing a release on GitHub.

Follow the steps in Updating releases/latest.

Follow the steps in Announcing a release.

Making point releases

Assuming a project board has already been created and all required work completed, the steps to make the point release are:

Create a new project board for the next point release.

Move any optional tasks that are not done to the next project board.

Check out the release branch (it should already exist).

For the

X.Y.Zrelease, the release branch is calledreleases/vX.Y. Forv0.15.1, you would check outreleases/v0.15:$ git checkout releases/v0.15

If a pull request to the release branch named

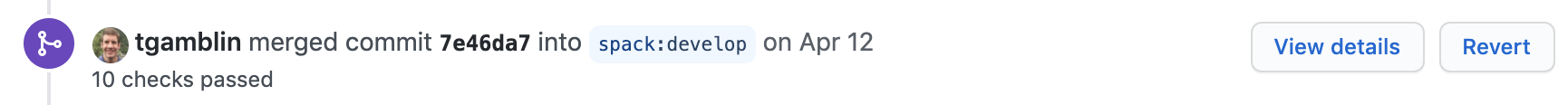

Backports vX.Y.Zis not already in the project, create it. This pull request ought to be created as early as possible when working on a release project, so that we can build the release commits incrementally, and identify potential conflicts at an early stage.Cherry-pick each pull request in the

Donecolumn of the release project board onto theBackports vX.Y.Zpull request.This is usually fairly simple since we squash the commits from the vast majority of pull requests. That means there is only one commit per pull request to cherry-pick. For example, this pull request has three commits, but they were squashed into a single commit on merge. You can see the commit that was created here:

You can easily cherry pick it like this (assuming you already have the release branch checked out):

$ git cherry-pick 7e46da7

For pull requests that were rebased (or not squashed), you’ll need to cherry-pick each associated commit individually.

Warning

It is important to cherry-pick commits in the order they happened, otherwise you can get conflicts while cherry-picking. When cherry-picking look at the merge date, not the number of the pull request or the date it was opened.

Sometimes you may still get merge conflicts even if you have cherry-picked all the commits in order. This generally means there is some other intervening pull request that the one you’re trying to pick depends on. In these cases, you’ll need to make a judgment call regarding those pull requests. Consider the number of affected files and or the resulting differences.

If the dependency changes are small, you might just cherry-pick it, too. If you do this, add the task to the release board.

If the changes are large, then you may decide that this fix is not worth including in a point release, in which case you should remove the task from the release project.

You can always decide to manually back-port the fix to the release branch if neither of the above options makes sense, but this can require a lot of work. It’s seldom the right choice.

When all the commits from the project board are cherry-picked into the

Backports vX.Y.Zpull request, you can push a commit to:Bump the version in

lib/spack/spack/__init__.py.Update

CHANGELOG.mdwith a list of the changes.

This is typically a summary of the commits you cherry-picked onto the release branch. See the changelog from 0.14.1.

Merge the

Backports vX.Y.ZPR with the Rebase and merge strategy. This is needed to keep track in the release branch of all the commits that were cherry-picked.Make sure CI passes on the release branch, including:

Regular unit tests

Build tests

The E4S pipeline at gitlab.spack.io

If CI does not pass, you’ll need to figure out why, and make changes to the release branch until it does. You can make more commits, modify or remove cherry-picked commits, or cherry-pick more from

developto make this happen.Follow the steps in Publishing a release on GitHub.

Follow the steps in Updating releases/latest.

Follow the steps in Announcing a release.

Submit a PR to update the CHANGELOG in the develop branch with the addition of this point release.

Publishing a release on GitHub

Create the release in GitHub.

Go to github.com/spack/spack/releases and click

Draft a new release.Set

Tag versionto the name of the tag that will be created.The name should start with

vand contain all three parts of the version (e.g.v0.15.0orv0.15.1).Set

Targetto thereleases/vX.Ybranch (e.g.,releases/v0.15).Set

Release titletovX.Y.Zto match the tag (e.g.,v0.15.1).Paste the latest release markdown from your

CHANGELOG.mdfile as the text.Save the draft so you can keep coming back to it as you prepare the release.

When you are ready to finalize the release, click

Publish release.Immediately after publishing, go back to github.com/spack/spack/releases and download the auto-generated

.tar.gzfile for the release. It’s theSource code (tar.gz)link.Click

Editon the release you just made and attach the downloaded release tarball as a binary. This does two things:Makes sure that the hash of our releases does not change over time.

GitHub sometimes annoyingly changes the way they generate tarballs that can result in the hashes changing if you rely on the auto-generated tarball links.

Gets download counts on releases visible through the GitHub API.

GitHub tracks downloads of artifacts, but not the source links. See the releases page and search for

download_countto see this.

Go to readthedocs.org and activate the release tag.

This builds the documentation and makes the released version selectable in the versions menu.

Updating releases/latest

If the new release is the highest Spack release yet, you should

also tag it as releases/latest. For example, suppose the highest

release is currently 0.15.3:

If you are releasing

0.15.4or0.16.0, then you should tag it withreleases/latest, as these are higher than0.15.3.If you are making a new release of an older major version of Spack, e.g.

0.14.4, then you should not tag it asreleases/latest(as there are newer major versions).

To tag releases/latest, do this:

$ git checkout releases/vX.Y # vX.Y is the new release's branch

$ git tag --force releases/latest

$ git push --force --tags

The --force argument to git tag makes git overwrite the existing

releases/latest tag with the new one.

Announcing a release

We announce releases in all of the major Spack communication channels. Publishing the release takes care of GitHub. The remaining channels are X, Slack, and the mailing list. Here are the steps:

Announce the release on X.

Compose the tweet on the

@spackpmaccount per thespack-twitterslack channel.Be sure to include a link to the release’s page on GitHub.

You can base the tweet on this example.

Announce the release on Slack.

Compose a message in the

#generalSlack channel (spackpm.slack.com).Preface the message with

@channelto notify even those people not currently logged in.Be sure to include a link to the tweet above.

The tweet will be shown inline so that you do not have to retype your release announcement.

Announce the release on the Spack mailing list.

Compose an email to the Spack mailing list.

Be sure to include a link to the release’s page on GitHub.

It is also helpful to include some information directly in the email.

You can base your announcement on this example email.

Once you’ve completed the above steps, congratulations, you’re done! You’ve finished making the release!